A young doctor’s compassion that moved Bangladesh

In a country where healthcare often feels stretched beyond its limits, one young trainee doctor has quietly ignited a spark of hope, not with grand gestures, but with unwavering empathy and relentless determination.

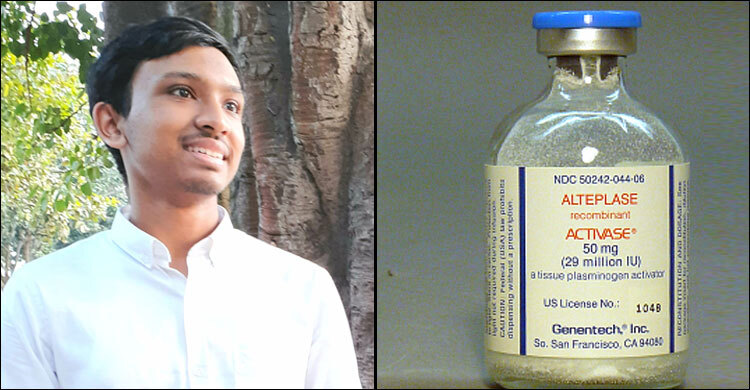

Shirsho Shreyan, an intern doctor at Rajshahi Medical College, has become a symbol of compassion after bringing 2,500 vials of Alteplase, a life-saving injection for stroke and heart attack patients, from the Netherlands, medicines worth an estimated Tk 17 crore, completely free of cost for patients in need.

Alteplase, a thrombolytic drug, is crucial in dissolving blood clots during the golden hour of stroke and acute heart attack.

Yet, its high price, around Tk 70,000 per vial, has long placed it out of reach for most ordinary families in Bangladesh.

Shirsho, witnessing the agony of patients and their families, refused to accept the status quo.

Driven by a deep sense of duty and humanity, he embarked on months of research, coordination, and negotiation with international health organisations and pharmaceutical suppliers.

His efforts culminated in the arrival of the medicine from the Netherlands, where it was made available through a humanitarian channel.

The impact was immediate. Lives that would have been lost are now being saved. Emergency rooms in Rajshahi and surrounding hospitals have begun administering the drug, offering a second chance to those on the brink.

His quiet heroism did not go unnoticed.

On Thursday, Health Adviser Nurjahan Begum publicly lauded the young doctor during the inauguration of new hostel facilities at Sir Salimullah Medical College in Old Dhaka.

“I came to know about Shirsho Shreyan’s initiative through the newspapers,” she said. “What moved me most was not just his medical knowledge, but the compassion and empathy he carries for people, the kind of humanity that should be instilled in every one of our sons and daughters.”

Her words, spoken with emotion, echoed across the gathering, a rare moment where policy and humanism converged.

The event itself was modest, no fanfare, no speeches. Just a plaque unveiling, a silent prayer for the well-being of students and patients, and a walk through the emergency ward where lives hang in the balance every day.

But it was in that simplicity that the message became clear: healthcare is not just about infrastructure or budgets, it is about people.

Shirsho’s story, Nurjahan emphasised, is a reminder of what young medical professionals can achieve when guided by conscience. “We train doctors to heal bodies,” she said. “But we must also nurture hearts that care.”

The day’s event also highlighted another critical issue, the living conditions of medical students. For years, students at Sir Salimullah Medical College had been studying and living in dilapidated, unsafe hostels, many of which were on the verge of collapse.

“How can one concentrate on saving lives when one fears their own roof might fall?” asked the Adviser.

Now, change is underway. Construction has begun on two new 12-storey female hostels and one 15-storey male hostel as part of a national initiative to build 19 new hostels across 10 government medical colleges.

Health Education Secretary Sarwar Bari, an alumnus of the college, said: “I was once a student here. I know the struggle. This isn’t just about shelter – it’s about dignity, safety, and space for creativity to grow.”

Director General of the Directorate General of Medical Education, Professor Dr Nazmul Hossain, added that the new hostels would include gyms, recreational spaces, and venues for cultural and academic activities aiming to create not just homes, but holistic environments for future healers.

Shirsho Shreyan never set out to be a hero. He simply saw suffering and chose to act.

His story has since gone viral, not because of media hype, but because it resonates with something deep within us: the belief that one person’s kindness can alter the course of many lives.

Students across medical colleges are now discussing how to replicate his model. Some are exploring partnerships with global health networks. Others are advocating for national stockpiles of critical medicines.

And in lecture halls and hospital corridors, the question is being asked: What kind of doctor do I want to be? Shirsho’s answer is clear: A doctor who sees patients not as cases, but as human beings.

As Health Adviser Nurjahan Begum concluded: “Let this humanity be instilled in every one of our sons and daughters.”