Entrepreneurs fume as BSTI's certification fee threatens businesses

In a system designed to guarantee quality, entrepreneurs across Bangladesh say they are being crushed, not protected.

At the heart of the controversy is the Bangladesh Standards and Testing Institution (BSTI), the national body responsible for certifying product safety, whose annual “certification mark fee” has become a major source of frustration for small, medium and even large businesses.

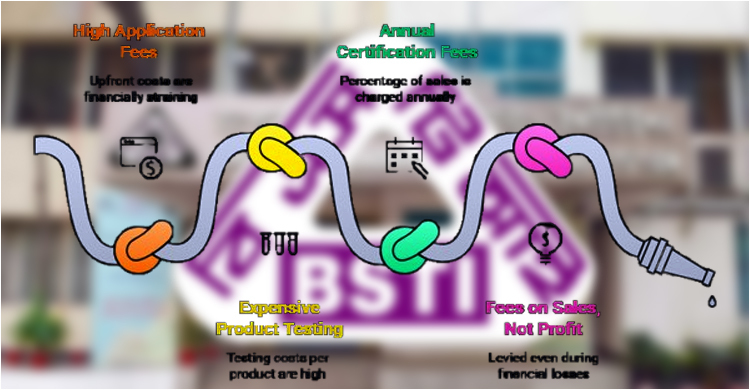

While BSTI’s mandate appears straightforward – issue licences, test products and enforce standards – the reality on the ground tells a different story: one of excessive fees, bureaucratic red tape and financial burdens so severe that many small manufacturers are either shutting down or selling unlicensed goods just to stay afloat.

“It’s not regulation, it’s extortion”

For Jihadul Islam, a food producer who asked to remain anonymous, the process feels like “a form of oppression.”

“To apply for a licence, they charge Tk 1,000 just for paperwork,” he said outside BSTI’s Tejgaon headquarters. “Then up to Tk 30,000 per product for testing. And that’s before you even get approved.”

But the real burden comes after approval.

Businesses are required to pay a certification mark fee at two tiers: 0.07% of annual sales, with a minimum of Tk 1,500 and a maximum of Tk 30 lakh per product; or 0.10% of annual sales, with a minimum of Tk 3,500 and a maximum of Tk 35 lakh.

Business owners argue that if a fee must be levied, it should be based on profit, not sales – especially since the current structure penalises even loss-making enterprises.

For example, a product generating Tk 150 crore in annual sales would incur a fee of up to Tk 35 lakh—a significant burden regardless of profitability. With around 13,000 licensed products under its purview, BSTI collects hundreds of crores of taka each year from these certification mark fees alone, making it a major source of the institution’s revenue.

Even more troubling, the fee is levied on sales, not profit. “Even if you’re making a loss, you still have to pay,” said Bidyut Hossain, a small-scale chutney maker. “For three variants, I’m looking at around Tk 25,000 just in application and test fees. I don’t even know if I’ll get the licence – and if I do, the annual fee could bankrupt me.”

One product, dozens of licences

The system multiplies the burden through extreme fragmentation. BSTI requires a separate licence for every variation by flavour, size or packaging.

Yakub Hossain of Mim Food Products wants to launch three types of chanachur in four packet sizes. That means 12 separate applications, each with its own test and fee.

“A sweet biscuit needs one licence, a salty one another, a barbecue another,” he said in frustration. “And 100g, 250g, 500g? Each gets its own file. What kind of fairness is this?”

This approach stifles innovation and product diversification – both essential for expanding non-traditional exports. “We export to Europe and the Middle East,” said Parvez Saiful Islam, Chief Operating Officer of Square Foods. “In those markets, certification is simpler, cheaper and often a one-off process. Here, it’s a recurring charge disguised as quality control.”

A lucrative monopoly, funded by business owners

Unlike most government revenues, BSTI’s fees do not go into the national treasury. Instead, they flow into the institution’s own fund a setup critics describe as a “self-financing empire.”

Last fiscal year alone, BSTI collected Tk 203.87 crore, with the certification mark fee forming a significant portion. With 13,000 licensed companies across 315 mandatory product categories, the institution gathers hundreds of crores annually, money entrepreneurs argue funds institutional overheads rather than public service.

“BSTI isn’t regulating, it’s profiteering,” said Shams Mahmud, former president of the Dhaka Chamber of Commerce & Industry (DCCI). “When 80% of investment comes from micro, small and medium enterprises, this kind of fee structure is disastrous for business growth.”

Fees higher than neighbours, deterring investment

A regional comparison highlights the problem further. According to a representative of a multinational operating across South Asia, Bangladesh’s licensing and renewal fees are significantly higher than those in India, Pakistan and Nepal.

“In other countries, fees are scaled to business size or charged once,” he said, speaking on condition of anonymity. “Here, they’re annual, mandatory and blind to whether you’re a start-up or a conglomerate. No wonder product diversity lags and ease of doing business suffers.”

The consequence? Many businesses skip licensing altogether. Unlicensed products flood the market, undercutting compliant firms and undermining the very safety standards BSTI claims to uphold.

Promises of reform, but will it happen?

BSTI’s Director (Administration), Md Nurul Amin, acknowledged the concerns: “We are actively considering reducing the certification mark fee. It is stipulated in the BSTI law, we are working to reduce it.”

Yet entrepreneurs remain sceptical. Past assurances have led to little change, and there’s no indication BSTI will overhaul its per-variant licensing model or shift fees from sales to profit, a move that would protect struggling businesses.

Shams Mahmud offered a stark assessment: “If laws are easy to follow, people will comply. If they’re imposed as a burden, evasion becomes the norm. The mindset of running public institutions by extracting money from business owners must end.”

For now, as small factories close and innovators retreat, Bangladesh’s ambition for a dynamic, diversified manufacturing sector remains stalled—weighed down by a system many say was meant to support, not suffocate, enterprise.