Engines of change: Inside Bangladesh’s Tk 12,000cr agro-machinery boom

At dawn in Manikganj, the quiet of the fields breaks with a growl of diesel. Abdul Karim, a 65-year-old farmer, steers his new power tiller across a stretch of golden stubble. A few years ago, this same patch of land would have needed two oxen and three back-breaking days to prepare. Now, it’s done before breakfast.

Karim’s story is far from unique. From Rangpur to Khulna, a quiet mechanical revolution is reshaping Bangladesh’s countryside — one engine, one gear, and one field at a time.

What began as a slow drift away from manual labour has turned into a national transformation worth Tk 12,000 crore, the size of Bangladesh’s booming agro-machinery market.

From labour shortage to mechanical surge

Ironically, the rise of machines stems from the disappearance of people. Rural youth are leaving the fields for factories and cities, and the cost of farm labour has risen sharply. Yet, food production keeps climbing. The reason? Metal is replacing muscle.

“Ten per cent of people are now feeding the other ninety per cent,” said Alimul Ahsan Chowdhury, President of the Agriculture Machinery Manufacturers Association. “Without mechanisation, this equation would collapse.”

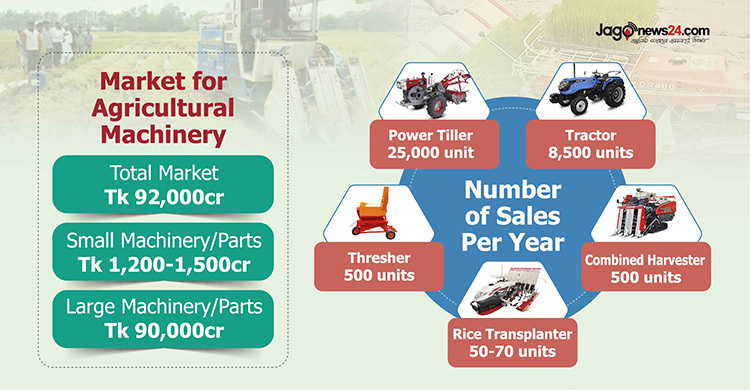

Industry figures show that the market for large agricultural machinery, including tractors, combine harvesters, reapers and power tillers, now stands at Tk 10,000 crore, while small-scale equipment accounts for another Tk 1,200–1,500 crore. And it’s growing by the season.

Market players and the import dilemma

Despite the surge, local manufacturers have yet to reap the biggest harvest. Less than a third of the market belongs to domestic firms. Most big machines, the heavy lifters of Bangladesh’s agricultural revolution, still come from Japan, China, India, and South Korea.

One company, however, has carved out a dominant position. ACI Motors, working in partnership with Japan’s Yanmar, leads in nearly every major segment.

“We hold 50% of the tractor market, 43% of combine harvesters, and 34% of power tillers,” said Dr FH Ansari, Managing Director and CEO of ACI Agri Business.

The company’s Manikganj factory, opened in 2018, has become a hub for assembling imported machinery and testing new models suited for Bangladesh’s diverse terrain.

Meanwhile, foreign players are setting up shop too. Several Indian, Korean and Chinese companies now have assembly operations within the country, betting that Bangladesh’s farms will continue to modernise fast.

A market still growing its roots

The Department of Agricultural Extension (DAE) says machinery is now used on 90-95% of farmland preparation, 90% of pesticide application, and 75% of threshing. But one area still resists mechanisation – planting. The machines are expensive, heavy, and often unsuitable for small plots, which make up most Bangladeshi farms.

Only 50 to 60 rice transplanters are sold annually, compared to 25,000 power tillers and 8,600 tractors.

According to a study by the Bangladesh Agricultural University, 80-95% of core farming stages, from irrigation to pest control, are mechanised, but post-harvest losses remain high. Poor logistics and lack of storage cause 40–45% of fruits and vegetables to go to waste.

“Mechanisation can’t succeed in isolation,” said M Masrur Riaz, Chairman of Policy Exchange. “It needs an ecosystem – skilled manpower, repair services, spare parts, and financing. Only 20% of machinery is made locally. With the right incentives, we could double that.”

Small players, big potential

At the grassroots, a quiet industrial base is taking shape. About 80 companies in Bangladesh are now manufacturing or assembling agro-machinery commercially, while another 1,000 small light-engineering workshops produce spare parts.

Most operate on a small scale, with limited access to capital or advanced technology. Yet, they represent a crucial opportunity — to localise production, reduce import dependence, and build a new industrial supply chain.

If that shift succeeds, it could unlock enormous value. Analysts estimate that localising just half of Bangladesh’s agro-machinery production could save hundreds of millions of dollars in import bills annually — while making machines cheaper for farmers.

The fields ahead

In a country where farmland is shrinking and labour is scarce, machines are becoming the new workforce. Tractors now plough more land than people ever could, and combine harvesters are taking the place of entire teams of reapers.

Still, the challenge lies beyond the field. Mechanisation must now connect to innovation — smart logistics, better financing, and a trained technical workforce.

Back in Manikganj, Abdul Karim wipes his brow and glances at the dark soil turned over by his tiller. “The land still needs hands,” he says with a smile, “but they’re made of iron now.”