Sea of greed: ‘Storages on water’ shake supply chain, wreck port operations

At the outer anchorage of the Chattogram Port, the horizon is no longer a clear line where the sky meets the Bay of Bengal.

Instead, it is a jagged, rusting silhouette of steel – a massive "ship jam" of mother vessels waiting for a relief that is not coming.

As of late January 2026, Bangladesh’s primary maritime gateway is grappling with a logistical stranglehold that threatens the nation's economic pulse.

While global supply chains often face natural disruptions, the current crisis at Chattogram is largely man-made.

A localised but devastating trend has emerged: the transformation of the nation’s lighterage fleet into "floating warehouses."

This practice, driven by a toxic mix of infrastructure deficits and the calculated greed of profit-monger traders, is paralysing port operations just as the high-demand season of Ramadan approaches.

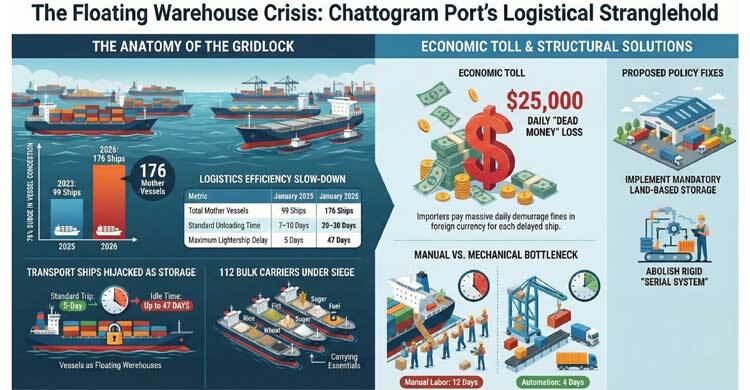

The anatomy of a gridlock: 176 giants in limbo

The numbers paint a bleak picture of a port under siege. On January 26, 2026, Chattogram Port recorded a staggering 176 mother vessels anchored at its jetty and outer anchorage – a massive jump from the 99 ships recorded during the same period in 2025.

According to Chattogram Port authorities, a total of 146 mother vessels were stationed at the port’s jetties and outer anchorage as of January 26, up from 99 vessels during the same period last year.

Port data show that on January 26, a total of 134 container and bulk cargo vessels were berthed at Chattogram Port. Of these, 12 were container ships, while 10 were LNG, LPG and petroleum fuel tankers. The remaining 112 bulk carriers were transporting rice, wheat, pulses, mustard, raw sugar, soybeans, fertilisers, iron scrap, cement clinker, coal, stone and plastic granules. Among them, 59 vessels were unloading cargo at the outer anchorage.

According to the port’s breakdown, the vessels currently at Chattogram Port include 53 general cargo ships carrying scrap and stone, 25 ships loaded with wheat and corn, 20 carrying cement clinker, seven fertiliser-laden vessels, five sugar carriers and two mother vessels transporting salt.

This is not just a bump in traffic; it's a structural collapse. Of these, 112 are bulk carriers laden with the lifeblood of the nation: rice, wheat, pulses, raw sugar, fertilisers, and cement clinkers.

The system relies on "lighterships" – smaller vessels that ferry cargo from these giants to inland wharves. But the conveyor belt has stopped. The crisis is best illustrated by the ships that time forgot.

The MV Anisa Jannat-1 has become a permanent fixture on the water; having left for Ashuganj with TSP fertiliser on December 10, it has been sitting, fully laden, for 47 days. Close behind is the MV Shubraj-8, carrying wheat to Hasnabad, stuck in unloading limbo for 46 days, and the MV Fazlul Haque-7, carrying essential corn, idling for 37 days. When a journey that should take five days stretches into seven weeks, the "transportation" vessel has officially been hijacked as a "storage" unit.

The ‘floating warehouse’ strategy

The crisis is rooted in a tactical shift by major importers and industrial conglomerates. Investigations and local allegations suggest that traders, lacking sufficient land-based silos or seeking to time the market for maximum profit, are simply refusing to unload their lighterships.

By keeping goods like wheat, fertiliser, and pulses on the water, importers avoid the overhead of land-based warehousing and can sell directly from the hull of the ship to buyers when prices peak.

SM Nazer Hossain, Chattogram Division President of the Consumer Association of Bangladesh (CAB), is blunt: "Big importers have turned lighterage ships into floating warehouses. There is a conspiracy to increase prices by creating an artificial crisis. The profit they gain from a price hike far outweighs the demurrage they pay for the mother ships."

Who holds the reins? A web of mismanagement

The management of this fleet is a complex web of private interests and overlapping authorities. There are currently 3,858 cargo-carrying lighters registered with the Department of Shipping, a number that should be more than sufficient. Yet, the reality is one of artificial scarcity.

WTCC sources said that as of Tuesday, January 27, a total of 630 lighterage cargo consignments were waiting to be unloaded at 74 wharves across the country. Of these, 134 consignments have been waiting for more than 15 days.

The highest number of lighters awaiting unloading was reported at Kanchpur, Hasnabad and Noapara in Narayanganj and Jashore districts.

Meanwhile, unloading operations are underway at several other points, including Jhalakathi, Nagarbari, Mirpur, Ruposhi, Bhairab, Sarulia, Hatabo, Patuakhali, Muktarpur, Aliganj, Rampal, Ashuganj, Karnaphuli River Sadarghat, C&B, Meghna, Bridgeghat, Shikarpur, Scan Cement, MI Cement, Palash, Pagla, Banaripara, Mongla, Akij Cement, Nitaiganj and Shiromani ghats.

The WTCC (Water Transport Coordination Cell): This body controls about 1,200 lighters and holds daily berthing meetings to allocate ships. However, they are currently paralysed. As of late January, 630 lighterages were stuck at various wharves, with 134 of them waiting for more than 15 days.

The Industrial Giants: Groups like Meghna, City, Abul Khair, and Bashundhara own private fleets. Ironically, even these groups are now seeking extra vessels from the WTCC because their own ships are tied up as storage units for their own stockpiles.

The Government's Ultimatum: The Ministry of Shipping has finally lost patience, issuing a five-day ultimatum to importers to clear their cargoes or face criminal charges. Chief Inspector Md Shafiqur Rahman noted that mobile courts are already handing out fines, but for a multi-million dollar trading syndicate, a fine is just another "cost of doing business."

The haemorrhage: $25,000 a day in ‘dead money’

For the mother vessels waiting at the outer anchorage, every hour of delay is measured in blood-red ink.

Shafiul Alam, Director of the Bangladesh Shipping Agents Association, warns that the shipping business is bleeding foreign currency.

Under normal circumstances, a 50,000-tonne mother vessel would complete unloading in 7 to 10 days. Today, that wait has stretched to 20 or 30 days. The cost of this inefficiency is staggering: importers are forced to pay between $10,000 and $25,000 in daily demurrage for each mother vessel. This is "dead money" – wealth exiting the country in foreign currency that provides no value to the consumer, only increasing the eventual price of the bread, oil, and sugar on their tables.

The reputation trap and the manual bottleneck

The implications extend far beyond the docks of Chattogram. Md Omar Faruk, Director of Administration at the port, admits that the increasing "average stay time" is creating a "negative image" internationally.

If global shipping lines perceive Chattogram as a "dead-end" where vessels are held hostage by local hoarding tactics, freight rates to Bangladesh will skyrocket, fueling a secondary wave of inflation.

Furthermore, the crisis has exposed a technological rot. While the world moves toward automated bulk handling, Chattogram still relies heavily on manual labour. Even with 60 labourers working around the clock, unloading a single lighter can take 12 days. With mechanical crane systems, this could be done in four. This "slow-motion" unloading provides the perfect cover for traders who want the delay, allowing them to claim "logistical issues" while they wait for market prices to climb.

A perfect storm: Fog, fertilisers, and finance

The WTCC has attempted to deflect blame, citing dense winter fog and the diversion of 140 vessels for government fertiliser transport. While these are factors, they are secondary to the primary disease: systemic hoarding. The port is effectively being used as a free parking lot for a few dozen powerful families, while the rest of the nation braces for the price hikes of Ramadan.

The path forward: From stagnation to flow

The government’s recent five-day ultimatum is a start, but industry veterans argue it is a bandage on a bullet wound. Real change requires:

Mandatory Land-Based Storage: Importers must be required to prove they have land-based storage capacity before being allowed to book lighterage.

Mechanical Modernisation: Moving away from the manual "basket-and-shovel" unloading method to automated conveyor systems.

Abolishing the "Serial System": Operators are calling for an open market system where ships move based on efficiency rather than a rigid, easily manipulated sequence.

As the sun sets over the Karnaphuli River, the lights of hundreds of stationary ships flicker like a second city on the water. For the people of Bangladesh, these lights don't represent a thriving trade – they represent a bottleneck.

The "floating warehouses" are a stark reminder that in the world of global trade, movement is life – and right now, the lifeblood of Bangladesh’s economy is sitting dangerously still.