Paper walls and toll gates: How the ‘NOC’ chokes Bangladesh’s new wave cinema

In the neon-lit shadows of Tejgaon, the Bangladesh Film Development Corporation (BFDC) stands as a monument to a bygone golden era.

But for a new generation of filmmakers, this "dream factory" has morphed into an expensive gatekeeper.

The biggest hurdle is not a lack of cameras or sets – it is a single piece of paper known as the No Objection Certificate (NOC).

As of early 2026, the cost of this "paper" has become a flashpoint for creative resistance. Independent producers, who once looked to the FDC for cameras and studios, now find the institution "unnecessary" yet unavoidable.

The paradox is simple: they do not use FDC’s services, but they cannot get their films certified without paying FDC for the privilege of saying they did not use them.

The Tk 20,000 'signature'

For decades, the BFDC was the sun around which all Bangladeshi cinema orbited.

If one wanted to make a movie, one rented its floors, used its labs, and hired its technicians. In that analogue era, the NOC was a logical audit tool to ensure a producer did not leave with unpaid bills.

Today, that logic has evaporated, but the fee has only grown.

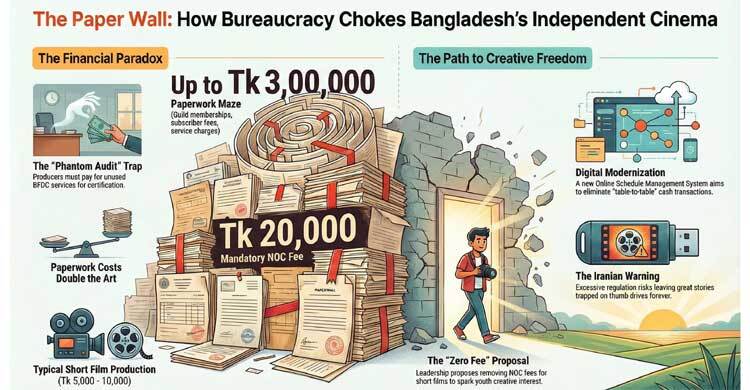

The financial landscape for independent creators is now dominated by a stark contrast in costs: while a typical indie short film budget might range from a mere Tk 5,000 to Tk 10,000, the mandatory BFDC NOC fee has climbed to Tk 20,000 – effectively doubling the cost of production just for an administrative clearance.

This is followed by a variable Certification Fee paid to the newly formed Bangladesh Film Certification Board, making the paperwork significantly more expensive than the art itself.

"Many producers finish making an entire short film within Tk 5,000," says young producer Golam Rabbani. "It is completely unfair to demand Tk 20,000 just for writing a few words on a pad without providing any service."

Analogue rules in a digital world

Filmmaker Qamrul Ahsan Lenin, a veteran of two decades, notes that the industry has undergone a radical shift that the FDC refuses to acknowledge. "Nowadays, films are being made using the mobile phone in hand," Lenin explains. "There is no need for separate infrastructural support for short films. Yet, the obligation to pay for an NOC remains as it did in the 1980s."

The frustration is particularly acute among short-film makers. Sohel Rana Boyati, known for the feature Naya Manush, started his career with shorts like Jal o Pani and Tear Gappo.

He reveals a heartbreaking reality: many of his award-winning shorts, though screened at international festivals, have never been officially "censored" or certified in Bangladesh because he couldn't afford the combined weight of the NOC and certification fees.

Producer and film teacher Matin Rahman said independent producers want the freedom to tell their own stories, but instead of encouraging that creativity, their space is being increasingly restricted. He believes the move could be an attempt to confine them within a fixed framework.

Speaking to Jago News, he said, “We have raised these issues many times, but no effective solution has been found.”

The 'phantom audit' and hidden tolls

The BFDC defends the fee as part of its administrative and audit process. But producers like Shimul Chandra Biswas and Rashid Palash view it as a desperate attempt by a fading institution to remain relevant.

The Authority Trap: Palash argues that the FDC has made itself redundant by failing to modernise, yet keeps these rules to "maintain its authority."

The Paperwork Maze: Beyond the NOC fee, filmmakers often find themselves aimlessly roaming a maze of guilds and associations. Some reports suggest that by the time a filmmaker clears director's guild memberships, subscriber fees, and service charges, the "paperwork" cost can spiral toward Tk 3,00,000.

A glimmer of reform?

The current leadership at BFDC seems aware of the rot. Masuma Rahman Tani, the Managing Director and a producer herself, has reportedly proposed a radical shift: zero fees for short film NOCs.

"I know very well the problems producers work under," Tani said recently. She has raised the issue in ministry meetings, arguing that removing the financial barrier for short films would spark a surge in creative interest among the youth.

Ahmed Mujtaba Jamal, director of the Dhaka International Film Festival, said young producers should not be burdened with excessive rules and regulations. “Things should be made easier for them. The requirement to obtain censorship clearance even to screen films at festivals is itself problematic,” he said, adding that at least festival films should be exempt from such fees.

Jamal said a proposal in this regard was submitted to the Film Commission, but the government was unwilling to take the risk. “If a new government comes and the issue is raised again, the problem may be resolved. However, public opinion must be built first,” he added.

However, Kamrul Ahsan Lenin does not support leaving the entire system completely unregulated. He proposes forming a small committee, if necessary, solely to review content and issue certificates. He believes this approach would both protect producers from harassment and maintain a reasonable regulatory framework.

Furthermore, the government has begun taking steps toward modernisation. Information and Broadcasting Adviser Syeda Rizwana Hasan recently inaugurated an Online Schedule Management System at BFDC. While this currently focuses on booking shooting floors, filmmakers are hopeful that it is the first step toward a digital NOC database that would eliminate the need to "go from table to table" with cash in hand.

The Iranian warning

Young director Sharif Nasrullah reminds the stakes. He cites the story of Iranian filmmaker Jafar Panahi, who famously smuggled his film out of the country on a thumb drive. "If Panahi had been told he needed an NOC and a stack of papers first, his film would have remained on that pen drive forever," Nasrullah warns.

The message from the filmmaking community is clear: if Bangladesh wants its stories told on the global stage, it must stop charging its storytellers for the right to exist.