A language hero forgotten: Ahmad Rafiq’s struggle at 95

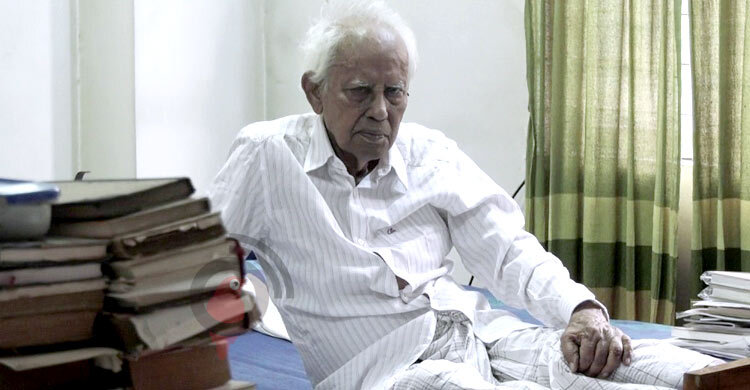

Ahmad Rafiq, a 95-year-old titan of the 1952 Language Movement, lies frail in a rented home in Eskaton, his body betraying the spirit that once marched for Bangladesh’s mother tongue. A doctor by profession, he chose literature over medicine, pouring his life into the cultural fight against Pakistan’s colonial oppression. Now, at the end of that life, he faces a bitter irony: the state he helped shape has left him to fend for himself.

“There is no regret for fighting,” Rafiq says, his voice faint but resolute, “but the state does not take care of it. No government has done it.”

His words, repeated like a refrain, echo a lifetime of sacrifice—and a present marked by abandonment. Financially strained, unable to afford proper treatment, the language martyr who once stood ready to die for his nation now spends his days lying down, thinking, his sight dimming, his hearing fading.

Rafiq’s story unfolds in stark contrast to the floral tributes flooding Shaheed Minars nationwide on Ekushey February. On February 19, Jago News’ Md Nahid Hasan visited him at 23/C Eskaton, finding a man sicker than the year before. “I can’t sleep properly,” Rafiq admitted after some coaxing. “I stay up all night, sleep a little in the morning. I can’t see well, can’t hear well, can’t eat much.” His meals are meagre—rice, fish, and vegetables at noon; a bite of cake or fruit at night—sustained by dwindling funds and sporadic help.

Once a homeowner in Uttara, Rafiq sold his property after his wife, microbiology professor SK Ruhul Hasin, died in 2006. Childless, he donated most of the proceeds to individuals and institutions, keeping only a modest sum he thought would suffice. “I didn’t think I’d live this long,” he reflects. Now, that generosity haunts him. Rent for his Eskaton house runs Tk 33,000 monthly, and with no steady income, expenses teeter on the edge of collapse.

Two caregivers, Md Abul Kalam and Chandrabanu, have stood by him—Kalam since 1989, Chandrabanu for 25 years. Once salaried attendants, they’re now family, though resources are thin. “A nephew sent money for a while, but he doesn’t check in anymore,” Kalam says.

Medical visits are a struggle: two people must carry Rafiq downstairs to a rickshaw, a cost and effort he can rarely muster. “It’s about one lakh taka a month,” Kalam estimates. “He has no income, no regular government aid.”

Rafiq’s disillusionment peaks with Samorita Hospital. “They promised care, showed it once, then billed me,” he scoffs. “Who trusts them?” Unable to rise easily, he misses the regular check-ups his worsening health demands. “Good treatment is needed,” he says, “but there’s a financial crisis, a crisis of going to the doctor.”

Abul Kalam, his voice steady where Rafiq’s falters, speaks for him: “If the government took responsibility, if a doctor checked him regularly, it’d be better.” It’s a plea rooted in decades of loyalty to a man who gave everything—only to be forgotten by the state he helped build.

As Bangladesh honours its language martyrs with flowers and song, Ahmad Rafiq’s quiet battle lays bare a painful truth: for some heroes, the fight never ends, and the silence of neglect stings louder than any tribute.