Extreme heat caused Bangladesh $24b loss in 2024

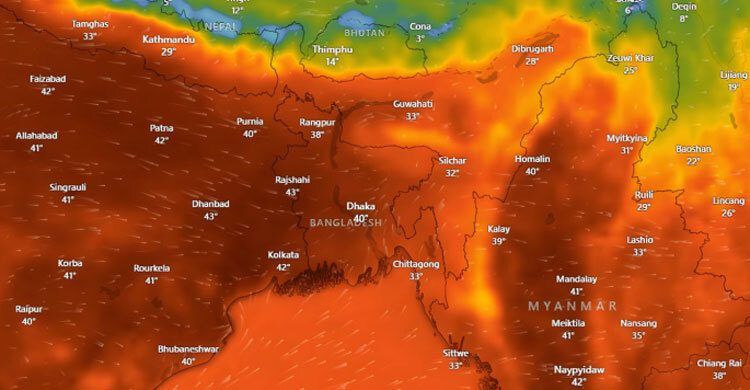

In a stark warning to policymakers and the global community, The Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change 2025 has revealed that Bangladesh lost $24 billion in income in 2024, equivalent to 5 per cent of its GDP, due to extreme heat undermining labour productivity.

The figure is not just a statistic; it represents millions of lost livelihoods, stalled development, and a nation on the frontlines of a climate crisis it did little to create.

The findings were unveiled at the national launch of the report in Dhaka, held at the BRAC Centre and co-hosted by the Centre for Climate Change and Environmental Research (C3ER) at BRAC University and The Lancet Countdown, with support from the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare’s Climate Change and Health Promotion Unit.

Heatwaves: From seasonal annoyance to economic saboteur

Once considered a seasonal inconvenience, extreme heat in Bangladesh has evolved into a systemic economic disruptor. In 2024, the average Bangladeshi endured 28.8 days of heatwave conditions—defined as periods when both daytime and nighttime temperatures exceed local thresholds for human health and comfort. Crucially, 13.2 of those days would not have occurred without anthropogenic climate change, the report states.

The consequences for the workforce have been severe. Heat stress reduced the country’s potential working hours by 29 billion – a 92 per cent increase compared to the 1990s. Outdoor labourers, particularly in agriculture, bore the brunt: 64 per cent of all lost work hours occurred in farming, fishing, and related rural sectors. With 55 per cent of total income losses concentrated in agriculture, a sector employing nearly 40 per cent of the workforce – the ripple effects extend far beyond fields and into household nutrition, children’s education, and rural debt cycles.

“Labour isn’t just about output; it’s about dignity and survival,” said Dr. Shouro Dasgupta, environmental economist and Senior Research Fellow at the Grantham Research Institute, London School of Economics, who presented the keynote analysis. “When a farmer can’t work past 10 a.m. because of heat, it’s not just a lost day—it’s a lost meal, a missed school fee, a deeper plunge into vulnerability.”

A surge in climate-sensitive diseases

Beyond economics, the health toll is accelerating. The report notes that the climate suitability for dengue transmission, a mosquito-borne disease already endemic in Bangladesh, has risen by 90% when comparing the baseline period of 1951-1960 to the decade of 2015–2024. Warmer temperatures, erratic rainfall, and urban water storage practices have created ideal breeding conditions for Aedes aegypti mosquitoes.

Meanwhile, air pollution, fuelled by brick kilns, vehicle emissions, and crop burning, remains a silent killer. It is now among the top three risk factors for premature death in the country, contributing to respiratory illnesses, cardiovascular disease, and low birth weight.

Compounding these threats is sea-level rise. In 2024, nearly 14 million Bangladeshis lived less than one metre above sea level, primarily in coastal districts like Satkhira, Khulna, and Barguna. These communities face a triple jeopardy: saltwater intrusion contaminating drinking water and farmland, increased flooding during cyclones, and displacement due to land loss.

From data to policy: A call for urgent action

At the launch event, Professor Ainun Nishat, Emeritus Professor at BRAC University and a leading voice on water and climate security, delivered a sobering message: “We are not preparing for a future crisis. We are living it. Every heatwave, every dengue outbreak, every flooded village is evidence that climate change is here—and it is hitting our most vulnerable first.”

Experts called for a three-pronged national response:

Climate-Resilient Agriculture: Promote heat-tolerant crop varieties, shift planting calendars, and expand access to irrigation and shade-based farming.

Labour Protection Policies: Enforce heat stress guidelines for outdoor workers, introduce flexible working hours during peak summer months, and expand social safety nets for informal sector workers.

Health System Strengthening: Scale up early-warning systems for heatwaves and disease outbreaks, train frontline health workers in climate-related illness management, and integrate climate risk into national health planning.

The global responsibility gap

While domestic action is critical, speakers stressed that Bangladesh cannot shoulder this burden alone. As a Least Developed Country (LDC) contributing less than 0.5% of global emissions, it remains disproportionately exposed due to geographic and socioeconomic vulnerability.

The Lancet Countdown report explicitly calls on high-income nations to deliver on unmet climate finance pledges, particularly through the Loss and Damage Fund and COP30 commitments. “Health adaptation in countries like Bangladesh requires predictable, grant-based funding—not loans that deepen debt,” Dr. Dasgupta emphasised.

Without such support, the report warns, Bangladesh risks erasing decades of progress in poverty reduction, maternal health, and education. A child in a heat-stressed household may drop out of school to work; a pregnant woman exposed to air pollution may give birth prematurely; a farmer may migrate to a slum after losing his saline-affected land.

The bottom line

The $24 billion loss is more than an economic metric—it is a measure of human suffering, systemic fragility, and urgent injustice. As The Lancet Countdown concludes: “Climate change is no longer a future threat for Bangladesh. It is a present public health and economic emergency.”

The question now is whether national resolve and global solidarity can rise to meet it—before the next heatwave, the next flood, the next lost generation.