In Dhaka, rent rises and lives unravel

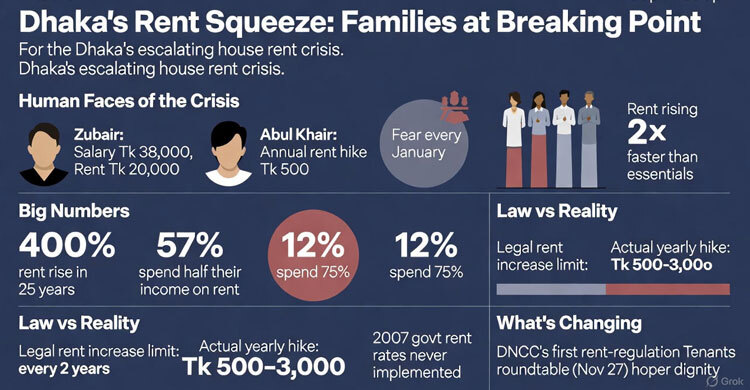

Every night, after the city finally settles into its familiar hum, Zubair Islam sits at the small dining table of his rented Shahjadpur flat. His salary is Tk 38,000 – the rent is Tk 20,000. By the time he covers basics for his five-member family, nothing is left.

“Every January, I wait for the house owner’s notice,” he says. “He raises rent without explanation – and if I ask why, he simply says: ‘Vacate if you want.’ We can’t live like this.”

For Zubair and millions like him, Dhaka’s rental market has become a silent humanitarian crisis — squeezing incomes, uprooting families, and eroding mental wellbeing.

The human cost of an unregulated city

In Wari, Abul Khair faces the same fate. Every year, his landlord adds Tk 500 to the rent – no consultation, no justification.

“Dhaka isn’t for the middle class anymore,” Abul says. “You can earn Tk 40–50 thousand and still feel poor. Rent alone eats half your income. We live on fear, not money.”

Stories like these echo across Dhaka – the city that pulls people in with opportunities but pushes them out financially.

According to the Consumers’ Association of Bangladesh (CAB):

• Dhaka rents have risen 400 per cent in 25 years

• Rent has grown twice as fast as the price of essentials

• 57 per cent of tenants use half their income just for rent

• 12 per cent spend a staggering 75 per cent on rent

These are not numbers – they are lives stretched thin.

The law that exists only on paper

In line with a High Court directive, several social organisations — including the Tenants’ Unity Council — have long been campaigning for the formation of a commission to enforce the House Rent Control Act. Their demands include making written contracts mandatory for all tenancy agreements, enforcing the area-based rent structure set by the government, and ensuring that rent payments are made through receipts or banking channels.

The then undivided Dhaka City Corporation set rent rates in 2007 for 775 areas of the capital – covering residential, commercial, and industrial zones as well as mud, semi-pucca and pucca houses, both within and beyond 300 feet of major roads. The rates ranged from Tk 5 to Tk 30 per square foot. However, the decision was never implemented.

The House Rent Control Act 1991 also outlines clear rules on rent increases. Section 16 stipulates that, unless major construction or structural changes are made, landlords cannot raise the base rent within a two-year period. This provision, too, is widely ignored. As a result, landlords routinely increase rent by Tk 500 to Tk 3,000 annually depending on the neighbourhood — in addition to yearly hikes in gas and electricity bills.

Rent keeps rising – Tk 500 in older areas, Tk 1,000-3,000 in middle-class neighbourhoods, and much higher elsewhere.

Most house owners follow one unwritten rule: “Take it or leave it.”

‘House rent must be normalised,’ speaks out tenants’ group

Tenant frustration has reached boiling point.

Md Ayatullah Akhtar, Secretary General of the Bangladesh Mess Association (BMO), says tenants face an annual mental battle.

“Dhaka’s tenants face a dilemma over house rent every new year. A major part of their income goes to rent. House rent cannot be increased unreasonably under any circumstances. The High Court’s directives must finally be implemented in 2026.”

His voice carries the collective exhaustion of the city’s renters – who say they have pleaded long enough.

A small ray of hope? DNCC steps in

For the first time, the Dhaka North City Corporation (DNCC) has called a roundtable discussion on tenant–landlord rights. Scheduled for November 27, the meeting aims to address how rent is determined, why it rises annually, and how both parties can coexist without fear or exploitation.

City officials say they want “fruitful discussions.” Tenants hope for something far more: dignity.

On DNCC’s official Facebook post about the meeting, the comments spoke volumes.

“Save the tenants,” one user wrote. “Uncontrolled rent is more dangerous than hardship.”

Another demanded area-based per square foot rent regulation.

For the first time in years, tenants feel their voices might matter.

DNCC Public Relations Officer Md Jobayer Hossain told Jago News, “We have invited housing organizations, welfare association leaders, and tenants from the DNCC area to the roundtable discussion. They will share their opinions on determining house rent, and based on those inputs, we will decide how to implement the policy in the future. The initiative aims to benefit both homeowners and tenants.”

But DSCC remains silent

While DNCC takes its first step, the Dhaka South City Corporation (DSCC) — home to 1.25 crore residents — has no such initiative.

When asked why, DSCC’s Chief Executive Officer Zahirul Islam said only: “People come to us when there’s a problem, and we solve it.”

But tenants say no one has solved their rent problems for decades.

Families cutting back on food, education, healthcare

Unregulated rent does not only strain wallets — it reshapes lives:

• Children are moved from better schools to cheaper ones

• Families buy lower-grade food to survive

• Medical visits are postponed

• Savings disappear

• People change homes so often that stability becomes a luxury

For tenants, January is not the start of a new year — it is the beginning of new anxiety.

As January approaches, fear returns

The annual rent-hike season is near.

Yet for the first time in many years, tenants feel someone is listening.

DNCC’s move may not fix everything overnight — but it opens the door to something Dhaka has long needed:

A housing system that acknowledges dignity.

A rental process grounded in fairness.

A city where survival does not depend on silence.

For Zubair, Abul Khair, and millions like them, even this small shift feels monumental.