From gifts to grift: Inside the hospital reagent scam

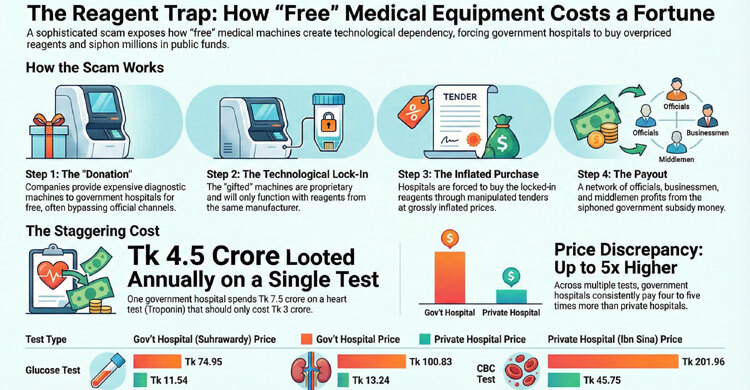

Behind the routine hum of hospital diagnostic labs lies a costly and largely unseen supply chain. Most testing machines and the chemicals they require – known as reagents – are imported from multinational companies through local agents. Unable to afford these expensive machines, hospitals are often given them free of cost. But there is a catch: the machines run only on specific reagents supplied by the same companies, creating a silent monopoly over the reagent market.

For years, the system went unquestioned. Over time, however, it has allegedly evolved into a lucrative web of corruption involving dishonest traders, political cadres, hospital insiders and middlemen, draining public funds through carefully crafted schemes.

After months of investigation, Jago News uncovers this hidden world in the first part of a two-part series – revealing how a business model in healthcare turned into a pipeline for corruption.

It was August 7, 5:15pm, when the National Institute of Cardiovascular Diseases (NICVD) in Sher-e-Bangla Nagar seemed to hold its breath. At Gate 1, in front of the South Block, a blue pickup truck stood quietly, its presence almost unremarkable at first glance. Yet what unfolded in the dimming light was anything but ordinary.

Cartons and packets of machinery were being unloaded in haste, their journey directed toward the Pathology Department near the CCU. The scene was cloaked in silence, but the silence itself felt heavy, unnatural. People were present, but their movements carried an air of secrecy. Something was off.

The unease sharpened when two familiar figures emerged from the shadows of the operation. Among those pushing the trolley were none other than Dr. Abdullah Al Mueed Khan, acting head of the Pathology Department, and Ganesh Chandra Tarafdar, the lab in-charge. Senior officials, men of authority, now reduced to porters of their own cargo. Why were they, instead of hired hands or company staff, maneuvering the heavy loads? Why the cautious glances, the deliberate avoidance of attention?

The activity stretched until 7:30pm, a full two hours of quiet urgency. Questions piled up, but the night offered no answers. In the darkness, inquiry was impossible.

The next morning, the mystery began to unravel. At the NICVD, after a day of probing, the story behind the clandestine delivery came into focus. Eight machines and diagnostic equipment had been smuggled in under cover of dusk, packed into cartons and ferried by pickup trucks.

The names behind the donation were familiar: ABC Corporation, Biotech Services, and SS Enterprises. Their intention, ostensibly generous, was to gift the machines to NICVD’s pathology department. Yet the hospital authorities had refused to formally accept them. And so, the machines entered through a “backdoor,” bypassing official channels, slipping into the system like contraband.

But why? Why would companies offer valuable machines for free? And why would hospital authorities cloak their acceptance in secrecy?

These questions became the starting point of a three-month investigation by Jago News. What emerged was a story not of generosity, but of corruption. The machines, once inside, became anchors for a larger scheme.

Reagents – the lifeblood of diagnostic testing – were being purchased at government hospitals at prices five times higher than the market rate. The “free” machines were not gifts at all, but bait. Once installed, they locked hospitals into buying reagents from the same companies, at inflated prices.

The result was staggering: government funds, meant for public healthcare, were being siphoned off in plain sight. Money from the people was being looted, masked by the veneer of donation.

The Machine, that reagent

“The global rule for diagnostic machines is that only the company’s machine and the reagent of that company will work. No other company’s reagent will work in that machine. So, no matter which machine is installed in a hospital, reagents from that company must be purchased for testing.”

The words of Shahriar Sourav, Managing Director of ABC Corporation, Bangladesh distributor of Mindray, cut straight to the heart of the issue. His statement, given to Jago News, explained the ironclad dependency built into diagnostic technology. Machines and reagents were inseparable; one could not function without the other.

It was this rule that opened the door to a cycle of profit. Equipment dealers, recognising the opportunity, began installing machines for free in government hospitals across the country. These “gifts” came with invisible strings attached. Once the machines were in place, hospitals had no choice but to buy reagents from the same companies.

At first glance, this practice seemed routine, even benign. Hospitals received expensive equipment without paying upfront, and companies secured long-term customers for their reagents. But as Jago News dug deeper, the picture grew darker. The investigation revealed that government hospitals were paying unusually high prices for these reagents – far above the market rate.

Over three months, reporters collected documents and evidence from seven government hospitals, five private hospitals, and four companies manufacturing equipment and reagents. With the help of two lab specialist doctors, two biochemists, and five technologists, the data was analysed. The findings were stark: reagents were being purchased at prices four to five times higher than the market rate, consistently, for years.

The scheme was simple but devastating. The cost of the “free” equipment was quickly recovered through inflated reagent sales. After that, it was pure profit – profit extracted from government funds meant to serve the public.

Jago News did not stop at the numbers. Further investigation uncovered another layer: middlemen. These third parties acted as conduits, ensuring that huge amounts of government subsidy money for public healthcare were siphoned off.

Interviews with three officials from equipment and reagent companies, four hospital representatives, and two middlemen painted a clear picture. The looting was not accidental; it was organised. Doctors, hospital officials, businessmen, middlemen, and politically influential figures were all part of the network.

Together, they exploited the tender system. Instead of straightforward contracts with suppliers, hospitals were forced into unnecessary and unreasonable tender processes. These tenders created space for manipulation, allowing the collusion to continue safely and without hindrance.

Abundance of gifts

When asked how many hospitals across the country had received donated machines, the Ministry of Health and the Directorate General of Health Services admitted they could not provide an answer. The data simply did not exist. What officials could confirm, however, was that there are 25,687 machines purchased with government funds nationwide. Of these, only a small proportion require reagents. Most of the reagent-dependent machines, they acknowledged, had arrived not through purchase but as gifts. At the private level, they had no information at all.

Doctors working in government hospitals described the formal process of donation. A company wishing to gift a machine must first submit an application to the hospital. That application is then reviewed by a committee, which issues its opinion. Based on this, the hospital director or supervisor makes the final decision. Only once consent is given can the machine be delivered and installed.

The investigation by Jago News revealed the scale of these donations. Across seven government hospitals, 35 machines had been gifted. Ten were found in the NICVD laboratory, another ten in Shahid Suhrawardy Medical College Hospital, eight in Dhaka Medical College Hospital, four in the National Kidney and Urology Institute, one in the outdoor laboratory of Rajshahi Medical College Hospital, one in the National Orthopaedic Hospital and Rehabilitation Institute, and one in the 250-bed TB Hospital in Shyamoli, Dhaka.

The pattern was clear. From medical colleges to specialist centres and district hospitals, donated machines had become commonplace. Companies were not merely offering gifts; they were competing with one another to place their machines inside government facilities.

Purchase at five times more

Government hospitals may receive machines free of charge, yet they continue to buy reagents through open tenders. On the surface this appears routine, but in reality, it is wholly unreasonable. The reagents required are specific to the company that manufactured the machine; no other reagents will work. Competitive bidding, therefore, is meaningless. A straightforward contract with the supplier or their local dealer would suffice. Instead, hospitals take a circuitous route, opening the door to manipulation. Here lies the mystery.

At this stage of the investigation, Jago News examined work orders for reagent purchases at Shaheed Suhrawardy Medical College and Hospital. One such order, issued on March 25, 2024 in the name of CSB Enterprise, revealed that chemical reagents and supportive equipment worth Tk 1 crore 48 lakh 18 thousand 78 had been purchased. These were intended for use in several machines, including biochemistry analysers, immunology analysers and cell counters.

Director Dr Mohammad Sehab Uddin confirmed that almost all of the machines had been donated free of cost.

The Biochemistry Analyser (Model AU 480), manufactured by the American company Beckman Coulter, is capable of performing 55 tests across nine types of blood. At Suhrawardy Hospital, it is used for glucose (FBS/RBS), creatinine, cholesterol, HDL, SGPT, TG and uric acid. Analysis of the hospital’s 2024-25 purchase list showed the cost per test: Glucose: Tk 74.95; Creatinine: Tk 100.83; Cholesterol: Tk 136.15; HDL: Tk 161.82; SGPT: Tk 128.21; TG: Tk 93.46; and Uric acid: Tk 114.80.

The same machine, donated by the same company, is also in use at the National Heart Hospital. Director Professor Dr Abdul Wadud Chowdhury confirmed this. Here, reagents are supplied by Radix Trade Limited. Work orders and test volumes for the 2024-25 fiscal year revealed markedly different costs: Glucose: Tk 45.27; Creatinine: Tk 53.86; Cholesterol: Tk 61.66; HDL: Tk 192.52; SGPT: Tk 75.26; TG: Tk 72.06; and Uric acid: Tk 85.24.

For comparison, Jago News analysed documents from Ibn Sina Medical College Hospital and Greenview Hospital in Dhanmondi. The differences were stark.

At Ibn Sina: Glucose cost Tk 11.54; Creatinine: Tk 13.24; Cholesterol: Tk 20.61; HDL: Tk 92.88; SGPT: Tk 23.20; TG: Tk 34.15; and Uric acid: Tk 21.60.

At Greenview Clinic: it was Tk 18.90 for Glucose test; Creatinine: Tk 22.03; Cholesterol: Tk 31.71; HDL: Tk 39.21; SGPT: Tk 16.95; TG: Tk 35.31; and Uric acid: Tk 28.28.

Similar calculations were found at Dhaka’s Zainul Haque Sikder Women’s Medical College Hospital and Uttara Modern Medical College Hospital, confirming the same pattern of inflated costs in government facilities.

To verify further, Jago News sought a quotation from OMC, the local dealer of Beckman Coulter’s Biochemistry Analyser (Model AU 480), on behalf of a private hospital. The figures were revealing: Glucose: Tk 11.38; Creatinine: Tk 10.25; Cholesterol: Tk 15.54; HDL: Tk 90.49; SGPT: Tk 22.18; TG: Tk 24.49; and Uric acid: Tk 24.56.

Conversations with the dealer also confirmed that these prices could be reduced further through negotiation.

Tk 4.5cr looted in one test

Among the arsenal of donated machines sits the Immunology Analyser, manufactured by the American company Beckman Coulter. Its market price ranges between Tk 30 and 40 lakh, depending on the model, and its domestic dealer is Oriental Marketing Corporation (OMC). The machine is capable of performing 42 tests across 10 categories.

At Suhrawardy Hospital, where it was gifted, it is used for T3, T4, FT3, FT4, TSH, Vitamin D and Testosterone.

Jago News obtained a work order for the 2024-25 fiscal year and, with the help of experts, analysed the purchase price of reagents and the number of tests conducted. The findings were striking. The cost of reagents and equipment per test was:

T3, T4, FT3, FT4: Tk 853.17

TSH: Tk 1,229.44

Vitamin D: Tk 302.99

Testosterone: Tk 896.38

By contrast, documents from the private Ibn Sina Hospital revealed far lower costs. There, reagents for T3, T4, FT3 and FT4 were priced at just Tk 209.43 per test, while TSH cost Tk 186.43.

The same machine can also detect whether a patient has suffered a heart attack, and to what extent, through the Troponin test. At the NICVD, OMC had donated the machine, but reagents were supplied by a third party, J Deluxe Channel Limited. Analysis of work orders showed that reagents and equipment for each Troponin test cost Tk 652.31.

The hospital conducts between 300 and 400 Troponin tests daily. Even at the lower estimate, this amounts to 9,000 tests per month, or 1,08,000 annually. The cost of reagents for this volume of testing reaches approximately Tk 7.5 crore.

In comparison, at the private Ibn Sina Medical College Hospital, the cost per Troponin test was Tk 272.62. For the same annual volume of 1,08,000 tests, the total expenditure was around Tk 3 crore. The difference is stark: government hospitals are spending at least Tk 4.5 crore more each year on reagents for a single test.

The disparity does not end with Troponin. At heart hospitals, reagents for T4, TSH and anti-pro-BNP tests were also found to be significantly more expensive than in private facilities.

Another routine test, conducted immediately after a patient is admitted, is the Complete Blood Count (CBC). The machine used for this is the Cell Counter, produced by several brands including Beckman Coulter, Sysmax and Mindray. These machines are expected to be present in nearly all of the 117 government hospitals at district level. The exact number is unknown, but most are believed to have been donated.

Here too, the evidence pointed to inflated costs. Documents from the private Universal Medical College Hospital showed that reagents for a CBC test on Sysmax machines cost Tk 45.75. A quotation obtained by Jago News from Sysmax’s domestic dealer, Biotech Services, placed the price at Tk 55 per test, with the possibility of further reduction through negotiation.

At Suhrawardy Hospital, however, the same test on a donated Sysmax machine cost Tk 201.96 – four times higher than in the private sector. At the NICVD, the figures were even more alarming: reagents for a CBC test on Beckman Coulter’s Cell Counter cost Tk 224.05.

“If such theft stops, healthcare will increase”

The government provides vast subsidies to ensure medical services for the public through its hospitals.

According to figures from the Directorate General of Health Services, a total of Tk 11,500 crore 44 lakh was allocated for hospital operating expenses across the country in the 2024-25 fiscal year. Of this, Tk 2,851 crore 17 lakh was earmarked specifically for the purchase of medical and surgical equipment (MSR) and chemical reagents.

Yet the investigation by Jago News revealed that much of this money has been misappropriated. The looting is complex, subtle, and largely hidden from view.

Dr Nazmun Nahar, Deputy Director (later promoted to Director) of the National Institute of Laboratory Medicine and Referral Centre, acknowledged the irregularities: “We also found such inconsistencies in government procurement in different hospitals while working. Each hospital buys a reagent or accessory at a different price. This should not happen. It should be at the same price everywhere. There needs to be a policy for this.”

She added: “If irregularities or corruption can be prevented, the healthcare coverage of the people can be further expanded with that money that the government allocates and subsidises. This requires sincerity and goodwill from everyone concerned.”

When approached, Health Secretary Md Saidur Rahman admitted surprise: “We have never seen such a thing before. Since you have brought it up, we will look into it now.”

Interim government’s health adviser Nurjahan Begum explained the reliance on donations: “We accept gifts because we do not have sufficient allocation to buy all our equipment. If someone is behind this, we will definitely catch them.”

From the business side, frustration was evident.

Ramzan Ali, Managing Director of Biotech Services, told Jago News: “We want to do business, not loot. Third parties come in and loot here. We do not get the opportunity to do business directly. A lot of trouble is caused.”

He repeated his grievance: “We want to do business, not loot. Third parties come in and loot here. We don’t get the opportunity to do business directly. A lot of trouble is caused.”