Source tax on savings certificates raised quietly, small investors hit hard

At the end of December, Shahnaz Parveen checked her bank account as she does every month. The profit from her savings certificates is a lifeline for managing her family’s daily expenses. But when she reviewed her January statement, she was stunned. The monthly profit from the same investment had dropped from Tk 2,736 in December 2025 to Tk 2,592 in January 2026. The amount was not drastically lower, but the question that troubled her was simple and serious: why did her income suddenly shrink?

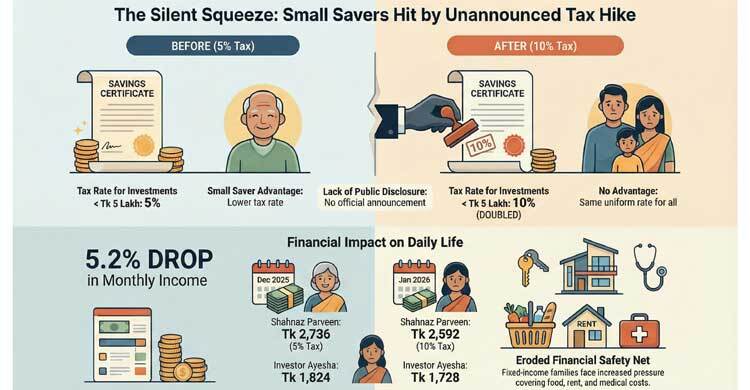

Her inquiry at the bank revealed an unsettling answer. For years, small investors like her who held savings certificates worth less than Tk 5 lakh paid a 5 per cent tax at source. That rate has now been doubled to 10 per cent, without any visible public announcement, circular, or notification. In effect, the government has raised taxes on small savers quietly, cutting into the income of people who rely on these returns to survive.

Savings certificates have long been considered a financial safety net for middle-class families, retirees, pensioners, and small savers seeking stable, low-risk returns. A relatively lower tax burden for smaller investments was one of the key incentives that attracted people to these schemes. With the new uniform 10 per cent source tax for all investors, that advantage has effectively been eliminated, disproportionately affecting those with modest savings.

Shahnaz Parveen says she feels blindsided by the move. “The tax on small investors like us has been increased silently. There was no announcement, no notice. Why was this decision taken in secret?” she asked. Her frustration reflects a broader sentiment among thousands of savers who are now seeing their monthly income decline without warning.

Another investor, Ayesha from Rampura, shared a similar experience. In December 2025, she earned Tk 1,824 in monthly profit from her savings certificate investment. In January, the same investment generated only Tk 1,728. Concerned, she contacted her bank and learned that the government had instructed financial institutions to deduct 10 per cent tax at source on all savings certificate profits, regardless of investment size. “Earlier, small investors paid 5 per cent and large investors paid 10 per cent. Now we are all paying 10 per cent,” she said. “It feels like the burden is being shifted onto those who can least afford it. Why are small investors being taxed more, while nothing new is being done for large investors?”

When asked about the issue, Md Rezanur Rahman, Deputy Director (Administration and Public Relations) of the National Savings Department, confirmed the change. He acknowledged that while investors with less than Tk 5 lakh previously paid 5 per cent source tax, a flat 10 per cent rate is now being applied to everyone. However, he could not specify when the decision came into effect or whether any official notification had been issued, adding to concerns about transparency and accountability.

This silent tax hike comes at a time when there is already uncertainty surrounding savings certificate profit rates. On December 31, the government issued a notification announcing a reduction in profit rates effective January 1. Yet, just four days later, that decision was withdrawn. As a result, the profit rates that were in force between July and December 2025 remain valid for the first half of 2026. On paper, returns appear unchanged, but in reality, many small investors are now receiving less money due to the higher tax deduction.

Currently, savings certificate investors are divided into two tiers. Those investing up to Tk 7.5 lakh fall into the first stage, while those exceeding that amount are classified in the second stage. Depending on the scheme, nominal profit rates range between roughly 11.82 per cent and 11.98 per cent at maturity. Yet for small investors, the increased source tax means their actual take-home earnings are shrinking, eroding the real value of these returns.

Under the Five-Year Bangladesh Savings Certificate, first-stage investors receive profit rates starting at 9.74 per cent in the first year, rising to 11.83 per cent in the fifth year if cashed before maturity. Second-stage investors receive slightly lower rates, starting at 9.72 per cent and rising to 11.80 per cent. Similar tiered structures apply to three-monthly profit-based savings certificates, pensioner savings certificates, family savings certificates, and post office fixed deposits, all offering competitive nominal returns. But with a uniform 10 per cent source tax now applied across the board, small investors are effectively losing a portion of the financial protection these schemes once provided.

Beyond the numbers, the political implications of this decision are significant. Raising taxes on savings certificates without clear public disclosure risks fueling perceptions that the government is targeting middle- and lower-income citizens while avoiding politically sensitive measures affecting wealthier investors. For retirees, pensioners, widows, and fixed-income families who depend on savings certificate profits to cover food, rent, and medical costs, the move feels less like fiscal policy and more like a quiet financial squeeze.

As living costs continue to rise and economic pressures intensify, critics argue that such silent policy shifts undermine public trust and deepen inequality. For small savers like Shahnaz Parveen and Ayesha, the issue is not only about lost income but also about fairness, transparency, and whether the state is protecting or penalising its most financially vulnerable citizens.