From white gold to wasted stock: Salt farmers quit as 3.5 lakh tonnes rot in pits

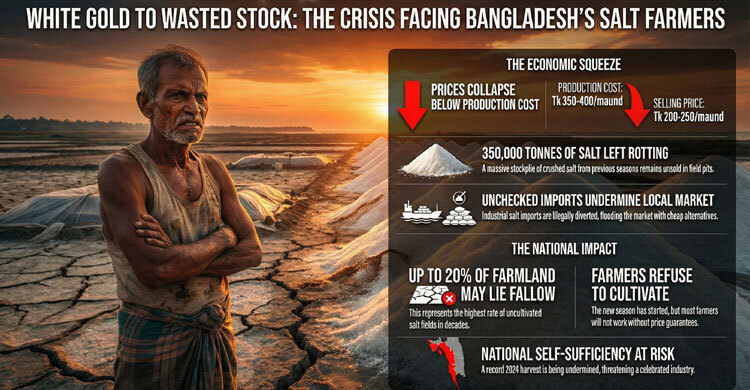

Bangladesh’s salt sector – long a symbol of self-sufficiency – is teetering on the brink of collapse as farmers refuse to begin the 2025-26 production season, leaving an estimated 3,50,000 tonnes of last year’s harvest rotting in open pits and threatening the livelihoods of more than a million people.

Cox’s Bazar and the coastal belt of Chattogram produce virtually 100 per cent of the country’s edible and industrial salt. Yet chronic low prices, high input costs and unchecked imports of supposedly “industrial” salt have pushed farmers to breaking point.

“Last year I spent Tk 350-400 to produce each maund but sold it for only Tk 200-250,” said Ali Akbar, a farmer from Khurushkul who recorded a Tk 2.5 lakh loss on two acres. “I will not step into the field again unless a remunerative price is guaranteed.”

Similar stories echo across Teknaf, Maheshkhali, Chakaria, Pekua and Kutubdia. Despite the season officially starting on November 1, only a handful of farmers in Kutubdia and Banshkhali’s Chhanua area have begun land preparation. Industry sources warn that up to 20 per cent of the 69,000 acres normally under cultivation could remain idle this year – the highest fallow rate in decades.

Harun Rashid, from Chaufaldandi Khamarpara in Cox’s Bazar Sadar, painted a stark picture of inactivity: “The salt production season starts in November. Last year, farmers were busy producing salt at this time (first week of December). And this year, let alone producing salt, the field has not even been prepared yet.”

Riduanul Haque, a farmer and businessman from Gomatli in Eidgaon, warned of long-term damage: “Seeing that salt is being sold at half the price after spending on everything including field lease, labour, and polythene, many have stored it in pits… This time, about 20 per cent of the fields are likely to be out of cultivation. If this continues for a few more years, many will gradually withdraw from salt cultivation.”

In Pekua, Muhammad Islam still has 1,500 maunds from the past two seasons unsold: “Farmers survive even if they get Tk 400-500 per maund. But for the last two years, a maund has been surviving at Tk 200-220. How can the family survive like this? I cannot bear the continuous losses. That is why I do not want to go to the field.”

Muksud Ahmed from Kutubdia vented his frustration: “Salt cultivation is on the verge of collapse today. Even though the country produces almost equal to the demand or in some years more than it, why do we have to import salt from abroad? Why is there no fair price for the salt produced by our sweat and labour?”

Stockpile crisis deepens

BSCIC officials confirm that approximately 3.5 lakh tonnes of crushed salt remain stored under polythene in field pits, unsold from the previous two seasons.

With current ex-field prices languishing at Tk 240 per maund – barely covering half the production cost – many farmers have chosen to hoard rather than sell at a loss.

Post-independence salt refineries in Islampur and other clusters have also slashed operations, further choking cash flow in the supply chain.

Imports undermine domestic producers

Farmers and mill owners accuse a powerful syndicate of importing industrial salt that is subsequently diverted into the edible-salt market at prices local producers cannot match.

“Why must we import any salt when domestic output either meets or exceeds annual demand of 2.5 million tonnes?” asked Muksud Ahmed of Kutubdia. “In 2024 we produced a record 24.38 lakh tonnes, the highest in 64 years.”

Government response falls short

At a high-level review meeting chaired by the Industries Secretary on November 11 at the Cox’s Bazar Deputy Commissioner’s Office, the ministry pledged “strict action” against misuse of industrial-salt import licences and promised to fix a fair price soon. Officials also floated plans for a dedicated salt-storage facility in the district.

Md Zafar Iqbal Bhuiyan, Deputy General Manager of BSCIC Cox’s Bazar, told this correspondent: “The delayed monsoon has slowed drying of shrimp enclosures, but the bigger issue is price. We remain optimistic that farmers will return once confidence is restored. New salt from Kutubdia and Chhanua should hit the market by mid-December.”

However, Shoaibul Islam Sabuj, organising secretary of the Cox’s Bazar Salt Farmers and Businessmen’s Sangram Parishad, warned that without immediate intervention on mill-owner syndicates, inflated land-lease rates and broker malpractice, “the entire sector faces irreversible damage”.

Production target at risk

This season’s official target stands at 26.18 lakh tonnes. With less than a month of favourable weather remaining before peak evaporation periods begin in March, missing even 15-20 per cent of cultivated area could wipe out hundreds of crores in farm-gate revenue and push edible-salt prices sharply higher for consumers by mid-2026.

As one Maheshkhali farmer, Joynal Abedin, put it: “The government buys paddy directly from our fields at a profitable price. Why is salt – produced with equal sweat under the same sun – treated as an orphan crop?”

Unless urgent price-support measures are announced within weeks, Bangladesh’s celebrated salt self-sufficiency may soon become a relic of the past.