‘Boycott America’ campaigns simmer in India amid tariff fallout

What began as a retaliatory trade salvo by US President Donald Trump has now ignited a full-blown economic nationalism campaign in India, threatening the dominance of American consumer giants from McDonald’s to Apple, Coca-Cola to Amazon.

In a sign of shifting economic sentiment, calls for a boycott of US products are gaining traction across social media, political rallies, and entrepreneurial circles marking a new front in the evolving US-India strategic relationship.

At the heart of the storm: Trump’s 50% tariff on Indian exports, a move seen in Delhi as protectionist and politically timed. While the Biden administration has since taken a more conciliatory tone, the damage to public sentiment has already been done. In a country where US brands have spent decades building loyalty, the backlash is now being weaponized as a tool of “economic sovereignty”.

The US-imposed tariffs targeting steel, textiles, and electronics have hit Indian exporters hard, particularly small and medium enterprises (SMEs) already grappling with global supply chain volatility. But the political response has been swift and symbolic: boycott American products.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who earlier described Trump a good friend, addressing a rally in Bengaluru, did not mention the US by name. But his message was clear: “It is time to prioritise India’s needs. We have built world-class technology. Now, let us use it for our own people.”

His words echoed across digital platforms, where hashtags like #BoycottAmericanProducts, #BackToBharat, and #SwadeshiRevival began trending. Influencers, entrepreneurs, and BJP-affiliated groups seized the moment, framing the boycott not just as economic resistance, but as national pride.

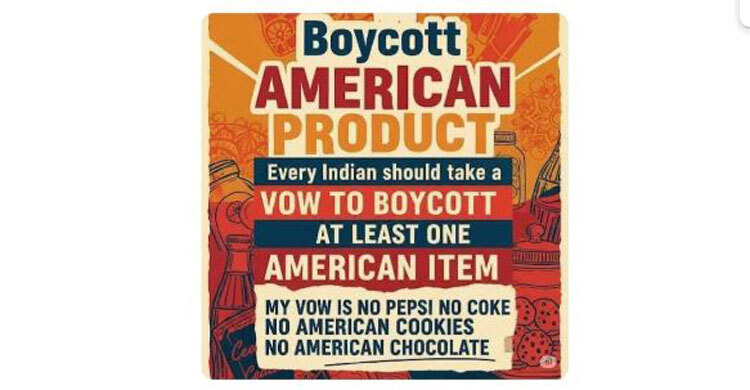

The Swadeshi Jagran Manch, the pro-Hindutva, nationalist economic wing of the BJP, has taken the lead. Organising small rallies across cities, the group is distributing WhatsApp-forwardable lists that replace foreign brands with Indian alternatives: Coca-Cola to Campa Cola (revived); *Colgate to Patanjali Dant Kanti; McDonald’s to Haldiram’s or Bikanervala; iPhone to Lava, Micromax, or the upcoming JioPhone.

Their social media graphics are bold and unapologetic: a “Boycott Foreign Food Chains” poster features the logos of McDonald’s, KFC, and Starbucks crossed out in red.

Yet, on the ground, the picture is more nuanced. At a McDonald’s in Lucknow, Rajat Gupta, 37, sipped his Rs 49 coffee and laughed at the idea of giving it up. “Tariffs are a matter for diplomats,” he said. “My McPuffs and coffee shouldn’t be dragged into it.”

He’s not alone. Millions of Indians, especially in urban centres, see US brands as symbols of modernity, quality, and aspiration, not foreign exploitation.

Beyond fast food and fizzy drinks, the movement is pushing for digital decoupling. On LinkedIn, Rahm Shastri, CEO of Indian mobility startup DriveU, declared: “India should have its own Twitter, Google, YouTube, WhatsApp, Facebook – just like China.”

While ambitious, the sentiment reflects growing unease over data sovereignty and platform dominance. With over 500 million WhatsApp users, more than any other country, India is both the US tech giants’ biggest market and their most vulnerable dependency.

Entrepreneurs like Manish Chowdhury, co-founder of Wow Skin Science, are turning the boycott into a nation-building mission. “We’ve queued up for products from thousands of miles away,” he said in a viral LinkedIn post. “Now it’s time to support our farmers, our startups, our ‘Made in India’ dream like South Korea did with K-beauty and K-food.”

The timing is delicate. India and the US are deepening strategic cooperation on Indo-Pacific security, defence, and technology – from the Quad to semiconductor partnerships. But economic nationalism at home could strain this alliance.

Yet, signs of continuity remain. Tesla opened its second Indian showroom in New Delhi on Monday, attended by officials from both the Indian Commerce Ministry and the US Embassy, a quiet but powerful signal that business ties endure.

This is not the first time India has seen a “boycott foreign goods” campaign. But unlike past movements, this one is being driven not just by politics, but by a new generation of entrepreneurs, digital campaigners, and consumers who believe India can and should compete on its own terms.