Yunus warns of an existential squeeze on Bangladesh

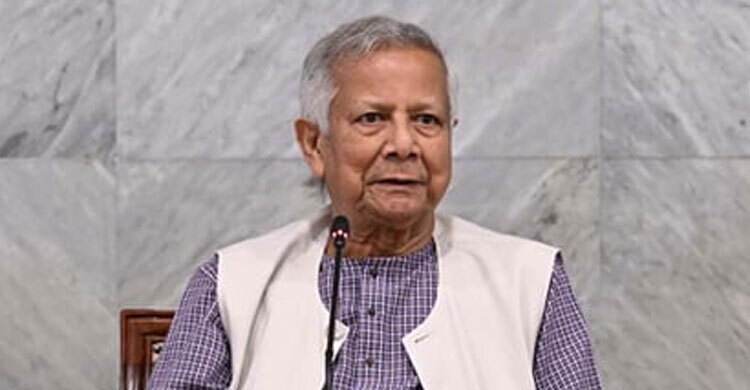

Bangladesh, one of the world’s most densely populated low-lying nations, is being pushed toward the brink by rising seas, shifting weather patterns and intensifying heat, Muhammad Yunus, the country’s chief adviser and 2006 Nobel Peace Prize laureate, told in an interview with The New York Times’ David Gelles.

Ahead of Yunus’ tour of New York to attend the UN General Assembly, The New York Times has put the interview in its ‘gift article’ section allowing its subscribers to share it with non subscribers.

Yunus, an economist and microfinance pioneer tapped to lead an interim government after last year’s political upheaval, said the country’s geography and demography make it especially vulnerable. “We have to make use of every little space we’ve got in order to feed ourselves,” he said. “But not only is our land sinking into the ocean; the water system brings saline water into the land because of the tide. And salinity eats up our cultivable land. So sum total is our land is getting squeezed.”

Those pressures, Yunus warned, are compounding social and economic strains in a nation where roughly half the population is under 26. “It’s a very young population. So they need a space to grow up and learn how to survive on this planet,” he said, arguing that climate change is not only an environmental crisis but a generational one.

Yunus framed the response to climate threats not only as a matter for governments and global summits, but as a personal and social project. While acknowledging the role of international fora such as the UN climate conferences, he said top-down funding alone is insufficient. “We try to solve everything by pouring money into it. That’s not the solution. I’m saying I have to change myself. That’s how the world will change,” he said.

Energy constraints, Yunus added, limit Bangladesh’s options for rapid decarbonization. The country lacks large hydropower potential and depends largely on solar; cross-border power projects — including supplies available from Nepal and Bhutan — have been hampered by transmission challenges that run through neighboring India, he said. Those geopolitical and infrastructural bottlenecks, he warned, leave Bangladesh exposed to both climate impacts and the strategic shifts of larger powers.

Asked about shifting international dynamics — from reduced US support for renewables under the Trump administration to the prospect of closer ties with China — Yunus was cautious, citing the constraints of his government role. Still, he made a broader moral appeal to wealthy nations. “Look, this is our home. You start a fire in your part of the home... You are destroying the whole home. Our life depends on what you do,” he said, urging greater responsibility from high-emitting countries.

Yunus, who rose to prominence by proving that very small loans can transform lives, suggested the same principle could apply to climate action: cumulative individual and community efforts can produce systemic change. “I won’t undermine the importance of the COP… But the solution has to be something which is not just the government giving instruction,” he said.

As Bangladesh navigates the twin challenges of climate stress and political uncertainty following last year’s unrest — which precipitated the formation of an interim government with Yunus as chief adviser — his message was stark: without major changes at the global level and grassroots shifts at home, the country’s narrow margins for survival will only shrink.